As society shifts to more demanding usages of wireless communication technology, it has become apparent that we have effectively reached a limit of orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (widely known as OFDM). This is due to delay and Doppler shifts appearing during data transmissions when a relatively high velocity can be seen between transmitting and receiving base stations. This same weakness of OFDM happens to be a strength of what became known as orthogonal time-frequency space modulation, or OTFS modulation.

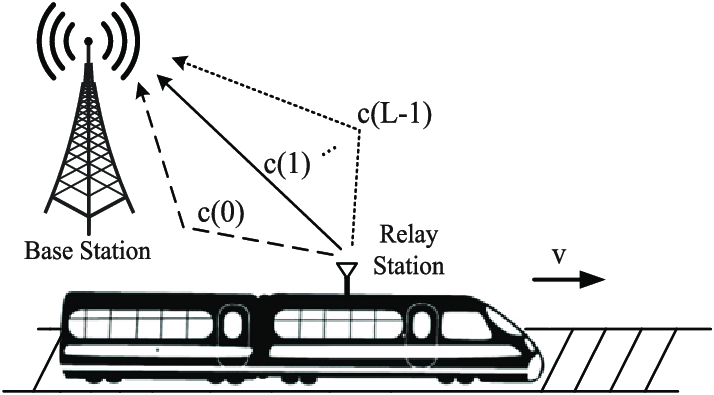

Figure 1: Multipath fading between a base station and a high-speed train [1].

OTFS quickly became well-known for its utility in high-speed environments due to its utilization of what’s called the delay-Doppler domain, but it was initially designed to create continuous data waveforms using the same time-frequency pulse shaping methods seen in OFDM. This was because it was originally found to be impossible to create a practical equivalent delay-Doppler space that remains orthogonal throughout all of that space, but this has since been shown to not be necessary anyway. Instead, a pulse shaping waveform can be created that holds for only the desired region of delay-Doppler space. With this in mind, OTFS has since been slightly modified and created what is now known as orthogonal delay-Doppler multiplexing (ODDM).

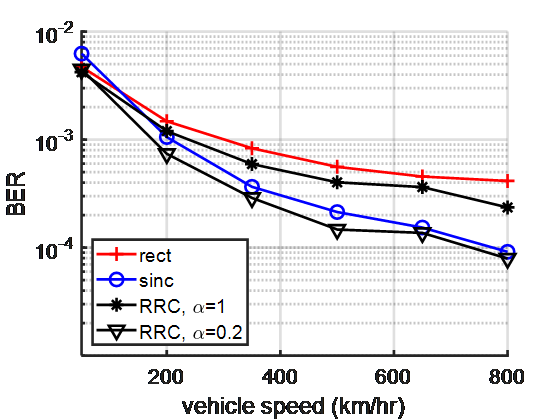

If ODDM is unfamiliar to you, please go here for a well-written primer on its fundamentals, but it works by essentially encoding data directly in the delay-Doppler domain, a subspace that does not experience fading as fast as the traditionally known time-frequency space. This resiliency is due to the delay-Doppler domain being effectively the time-frequency domain with a finer resolution, leaving the data relatively unaffected by the velocities of the receiver and transmitter. In fact, a high relative velocity actually compliments ODDM, as seen in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Resiliency of ODDM to vehicular velocity under different pulse shapes.

However, in using a data grid in the delay-Doppler domain, itself a finer-resolution time-frequency domain, the space used for data transission goes underutilized. If one were to sequentially send ODDM data frames, this multiplies the total time-domain duration by the number of data frames, but there is no immediately apparent analog to extending the total frequency-domain bandwidth. Of course, this could be achieved by simply shifting the frequency of each data frame, but this could only be achieved by implementing as many transmitters as frequency-levels you required. A desirable system is one that fully takes advantage of time, frequency, delay and Doppler domains while doing so on a single transmitter, to allow for mass implementation.

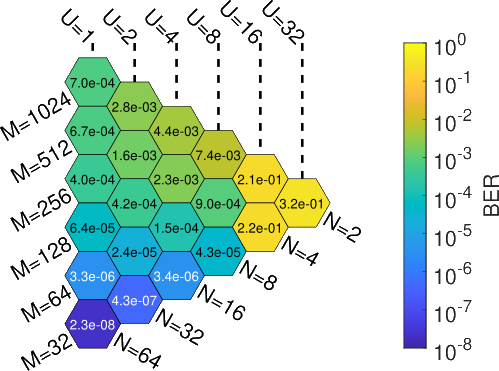

Tri-orthogonal delay-Doppler multiplexing, or TODDM, is a modulation scheme designed to be such a system. By encoding delay, Doppler and frequency diversity in the pulse shaping level, a TODDM system can fully utilize all four domains as needed, given the constraints of the working environment. Below, Figure 3 shows all possible configurations of M subcarriers, N time symbols and U frequncy levels for a 2048-symbol time-frame (M×N×U=2048). For every level of N (holding frame time duration constant), there exists a combination of M and U that gives the lowest bit error rate (BER) at high signal-to-noise ratios.

Figure 3: Hexgrid of BER for possible configurations, 2048 symbols per time-frame, \( E_b/N_0 \) = 24dB.

To learn more, visit our GitHub project page above to simulate it for yourself and better understand its strengths and weaknesses over OTFS and traditional ODDM.